Help us discover the unknown in inflammation

From 5th century BC to now: inflammation through the ages

People have known about inflammation and why it develops for thousands of years. Hippocrates, the ‘father of medicine’, described the diagnostic symptoms for inflammation and first coined the terms sepsis and oedema in the 5th century BC. Aulus Cornelius Celsu was a Roman encyclopaedist who recorded the signs of inflammation as redness, swelling, warmth and pain, known as Celsus tetrad of inflammation, during the 1st century AD. However, it wasn’t until the 16th century that scientists could visualise inflammation in the circulatory system with the invention of the microscope, and over time, were able to link inflammation to neurological and cardiovascular disorders, cancers and diabetes. In 1899, Aspirin was the first anti-inflammatory medicine introduced to treat many conditions, followed by corticosteroids in the 1950s to 1960s. Professor Charles Janeway Jr identified that pattern recognition receptors initiate inflammation in 1989, while the inflammasome was discovered in 2002 by Dr Jürg Tschopp. At IMB, we’re continuing the tradition by advancing our knowledge about inflammation and why it affects so many people.

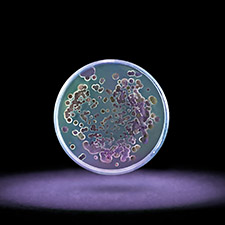

The inflammasome.

The inflammasome.

If the body’s cells are injured or infected, inflammation is switched on by the inflammasome. This super protein complex produces chemicals that make blood vessels porous so macrophages and phagocytes can move into the affected area, clear away the cellular debris and attack any bacterial infection, allowing the healing process to begin. But sometimes the inflammasome’s switch dysfunctions and when it doesn’t turn off, or when it is activated inappropriately, the inflammation cycle continues. Instead of healing, inflammation attacks the body, resulting in chronic ongoing pain and the onset of disease.

Arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disease.

Arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disease.

Why are we hearing more about inflammatory diseases than ever before? The 21st Century is a time of progress and achievement. But modern-day stresses to the body through environmental impacts, lifestyle habits and our own genetic imprint can detract from a healthy life. Potential enemies that prompt chronic inflammation include: specific toxic chemicals ingested by breathing, touching surfaces or wound exposure, with air pollution heightening the chance of heart attack and stroke; stress, depression and anxiety spark cortisol production - the flight or fight hormone - which can interfere with the body’s response to inflammation; bad dietary choices can lead to type 2 diabetes and obesity; asbestos fibres and silica particles cause lung diseases, eventuating in scarring to lung tissues; cigarette smoke causes cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and can lead to rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease or atherosclerosis.

Smoking is a contributor to inflammatory diseases such as cardiovascular disease.

Smoking is a contributor to inflammatory diseases such as cardiovascular disease.

All of these factors mean inflammation-related diseases are the number one cause of death globally. At the Institute for Molecular Bioscience, we’re progressively understanding the mechanism of inflammation to strike at the core of disease such as cardiovascular, infection, cancer, injury related, respiratory, digestive, dementia, Alzheimer’s, diabetes and sepsis. It is not just the physical effects of inflammation driving our work, it is also the social, economic and emotional cost to people in the community. For example, Australians lose $3.1 Billion per year to hospital treatment and time off work because of inflammatory bowel disease. Understanding inflammation and finding ways of prevention not only increase the discovery rate of specific therapeutic pathways but provides evidence-based advice for people to make alternative lifestyle choices and avoid chronic inflammation where possible.

Australians lose $3.1 billion per year due to inflammatory bowel disease.

Australians lose $3.1 billion per year due to inflammatory bowel disease.

Our discoveries about the mechanisms of inflammation are spurring on the development of life-changing therapeutic treatments for many people around the world. Professor Grant Montgomery’s work is helping to advance knowledge about endometriosis and how to treat this debilitating disease experienced by 1 in 9 women globally. Associate Professor Mark Smythe is looking for anti-inflammatory molecules inspired by molecules from killer venoms, while Professor David Fairlie and colleagues are uncovering new pathways to treat the inflammatory response of asthma. Professor Kate Schroder is understanding the inflammasome, the molecular machine with the potential to flip the switch on chronic inflammation. And Professor Matt Sweet is finding ways to prevent inflammation from happening, by disrupting the power supply to macrophages from glycolysis and stop their activity, while also exploring the role of inflammation in liver disease.